Yann LeCun’s vision for the future of AI, beyond LLMs and AGI.

Comparatives

Dernière mise à jour :

December 22, 2025

5 minutes

On March 13, 2024, the European Union adopted the AI Act, the world's first global regulation dedicated to artificial intelligence, marking a historic turning point comparable to that of the GDPR. From 2026, all companies developing, integrating or using AI systems in Europe will have to prove that their models are traceable, explainable and controlled. The aim is to put an end to AI that is opaque, uncontrolled, and legally risky. Automations without supervision, decisions that are impossible to explain, “black box” models: what was tolerated yesterday is becoming a major legal, financial and reputational risk. The AI Act thus redefines the rules of the game and imposes a new strategic question on businesses: who will be ready in time, and who will discover the cost of non-compliance too late?

The European AI Act frames AI through risk. Learn what's changing for businesses, sanctions, and decisions to make.

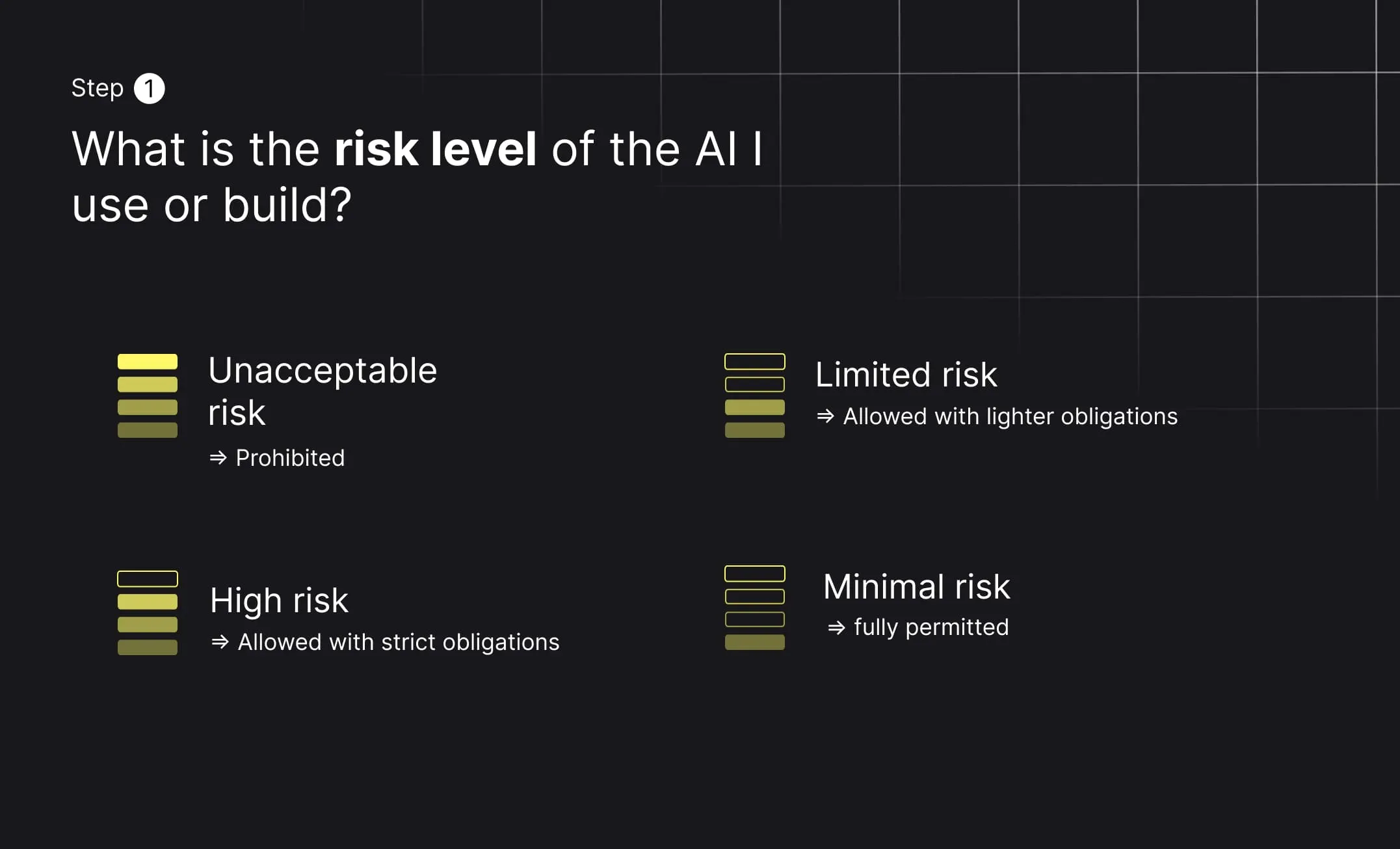

The AI Act does not regulate artificial intelligence in a uniform way. Instead, it is built on a simple but decisive principle: the higher the potential impact of an AI system on individuals, rights, or society, the stricter the regulatory requirements.

This marks a clear shift compared to previous technology regulations. The key question is no longer whether a company uses AI, but how, where, and with what consequences. In other words, the regulation focuses less on the technology itself and more on its real-world use and effects.

Many organizations talk about the AI Act without having actually read it. That is hardly surprising. The regulation is long, dense, and highly technical. Yet understanding its operational logic does not require reading every article line by line.

Even the “high-level summaries” published by the European Commission remain difficult to digest for product, engineering, or business teams. This is why a more practical approach is to reason through the AI Act using a series of structured questions, starting with risk classification.

At the heart of the AI Act lies a four-tier risk classification. This is the starting point for any compliance analysis.

Unacceptable risk – prohibited

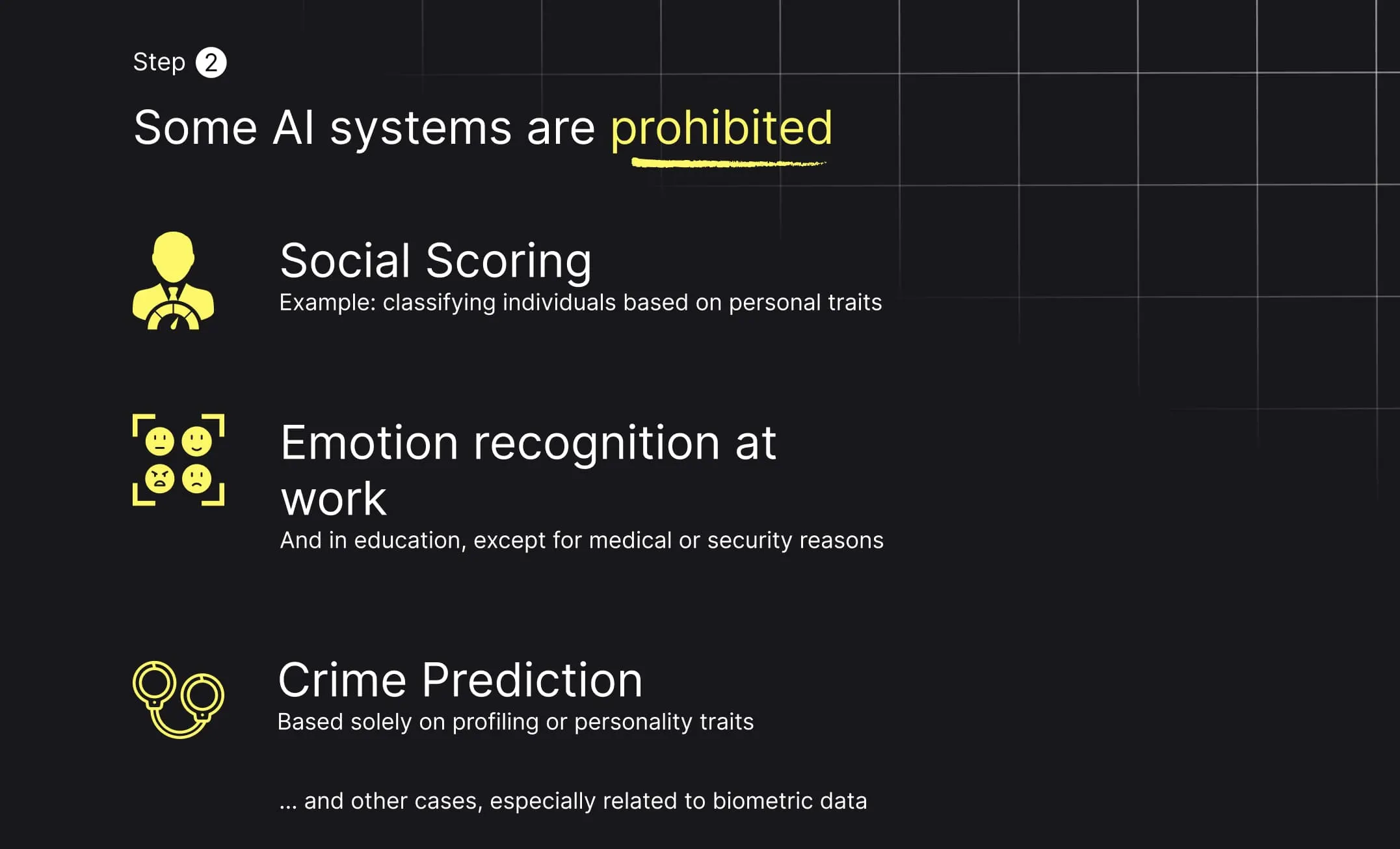

Certain AI uses are outright banned because they are considered incompatible with fundamental rights. These include social scoring, predictive policing based on profiling, real-time facial recognition without strict safeguards, and emotion recognition in the workplace or in education.

High risk – allowed but strictly regulated

High-risk systems are permitted, but only under strict conditions. They cover use cases where errors or biases could have serious legal, financial, or social consequences, such as healthcare, recruitment, credit, insurance, justice, critical infrastructure, or migration management. These systems are subject to strong governance and compliance obligations.

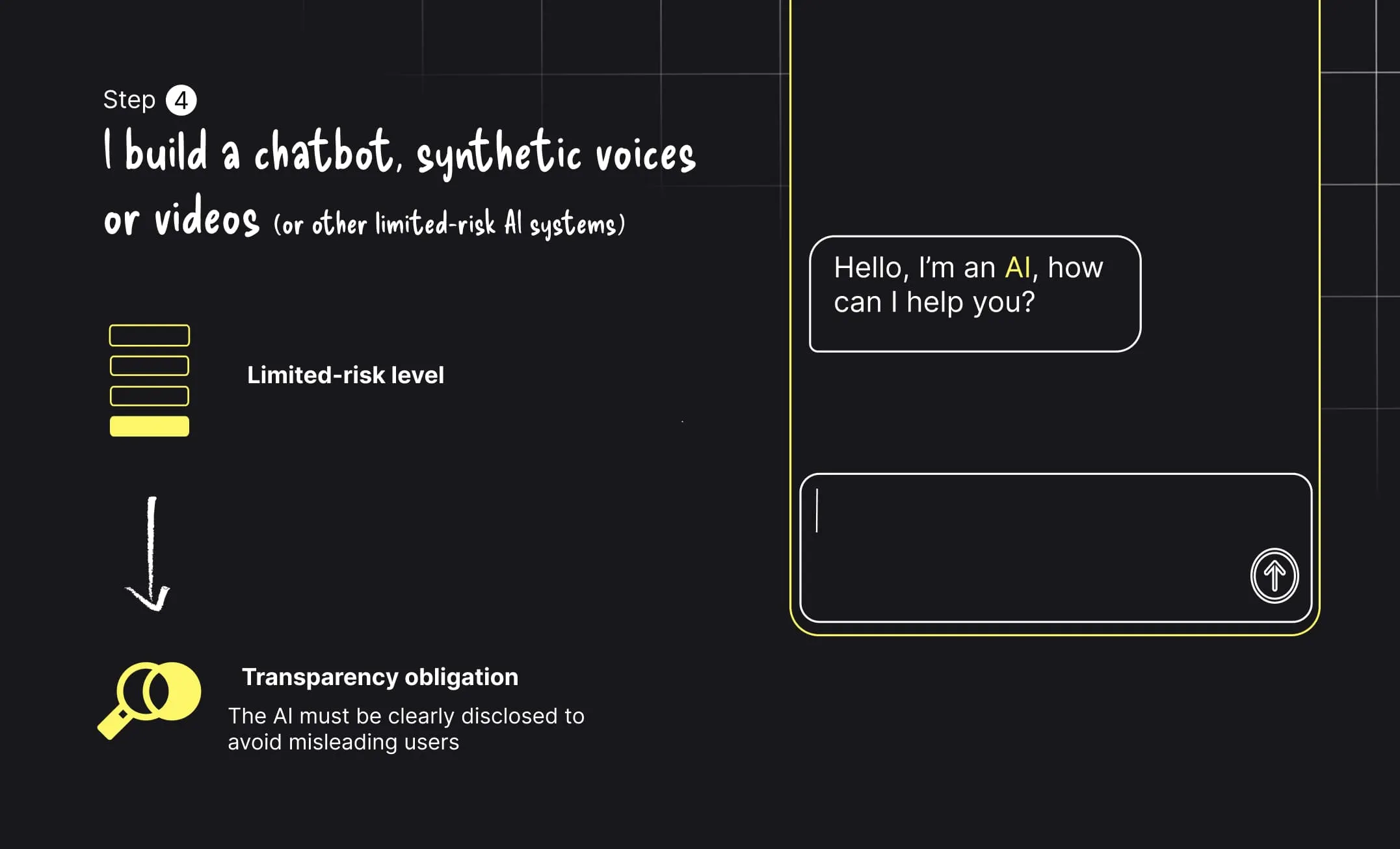

Limited risk – transparency obligations

When AI systems interact directly with humans, users must be clearly informed. This applies to chatbots, synthetic voices, and AI-generated or manipulated content.

Minimal risk – free use

Low-impact use cases such as spam filters, basic recommendation engines, or video games are not subject to specific regulatory constraints.

Before diving into complex compliance efforts, the AI Act allows organizations to rule out certain scenarios early on. If a system falls under prohibited practices, compliance is not an option; the system must be abandoned or fundamentally redesigned.

For most companies, this step is reassuring. If your AI does not score citizens, predict crimes based on personality traits, or infer employee emotions, you can move forward. This clarification helps reduce much of the anxiety surrounding the regulation.

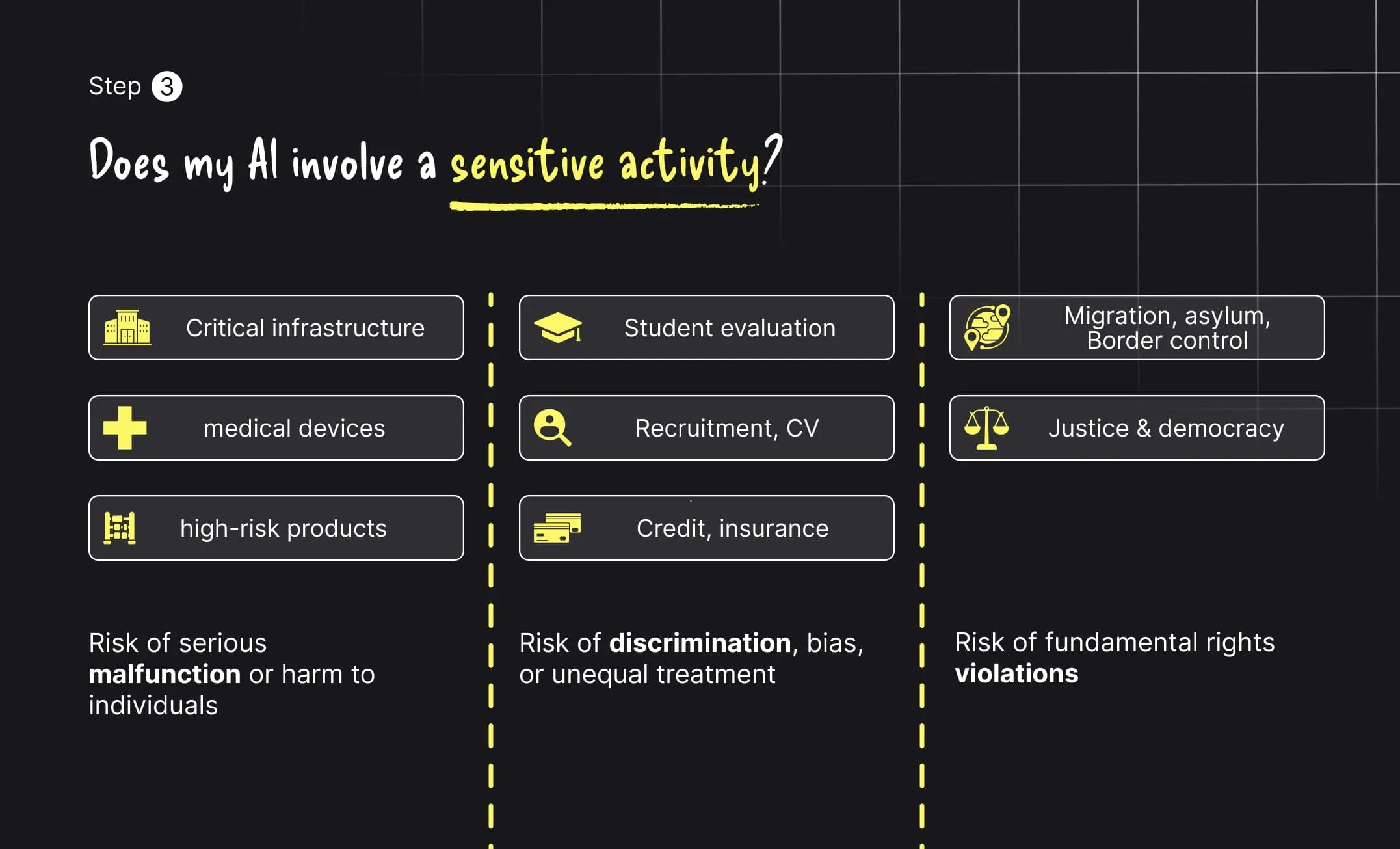

The most critical zone begins when AI systems are deployed in so-called sensitive activities. In many real-world scenarios, these systems rely on large volumes of unstructured or semi-structured documents, such as medical records, identity documents, financial statements, or administrative files. Processing these inputs typically requires an OCR step to convert raw documents into usable data, which further amplifies the importance of accuracy, traceability, and human oversight under a regulatory framework like the AI Act.

Critical infrastructure, medical devices, and high-risk products expose individuals to physical harm. Systems used for student evaluation, recruitment, CV screening, credit, or insurance carry risks of discrimination and unequal treatment. AI applied to migration, justice, or democratic processes directly affects fundamental rights.

In these contexts, AI is no longer a simple optimization tool. It becomes a decision-making actor that must be tightly controlled.

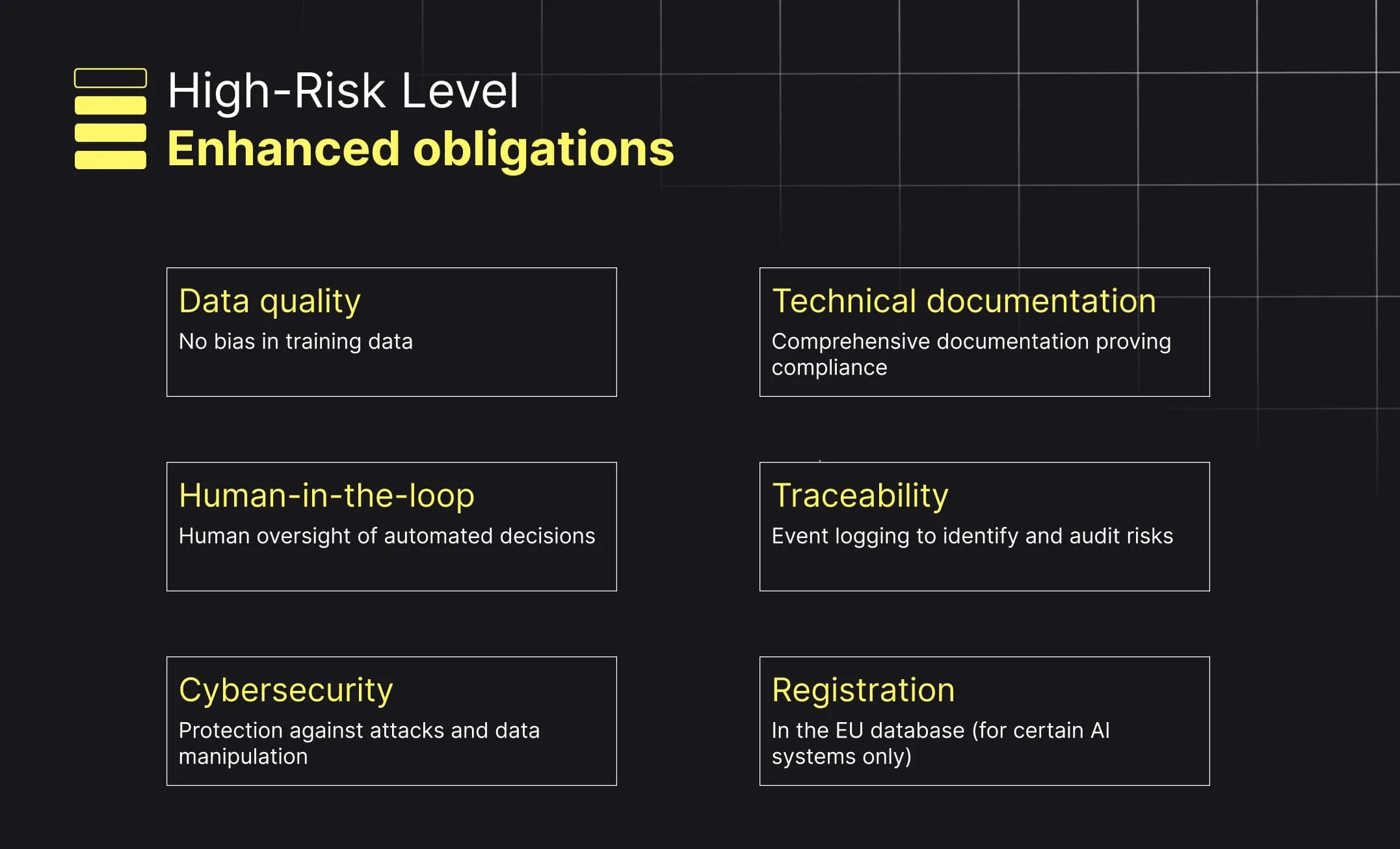

When an AI system is classified as high risk, the AI Act leaves little room for interpretation. Compliance is based on clearly defined operational requirements.

Organizations must demonstrate data quality and bias mitigation, maintain comprehensive technical documentation, ensure meaningful human oversight, enable decision traceability through logging, protect systems against cyber threats, and, in some cases, register models in a European database.

These requirements fundamentally change how AI systems are designed. They favor structured, auditable, and governable architectures over opaque “black box” approaches. This shift aligns closely with the principles of intelligent document processing, which focus on traceability, explainability, and operational control across complex AI-driven workflows.

Not all AI projects fall into the high-risk category. Many common generative AI use cases are classified as limited risk.

In these situations, the core requirement is straightforward but non-negotiable: transparency. Users must be informed when they are interacting with an AI system or consuming AI-generated content. The goal is to preserve trust and prevent users from being misled, intentionally or not.

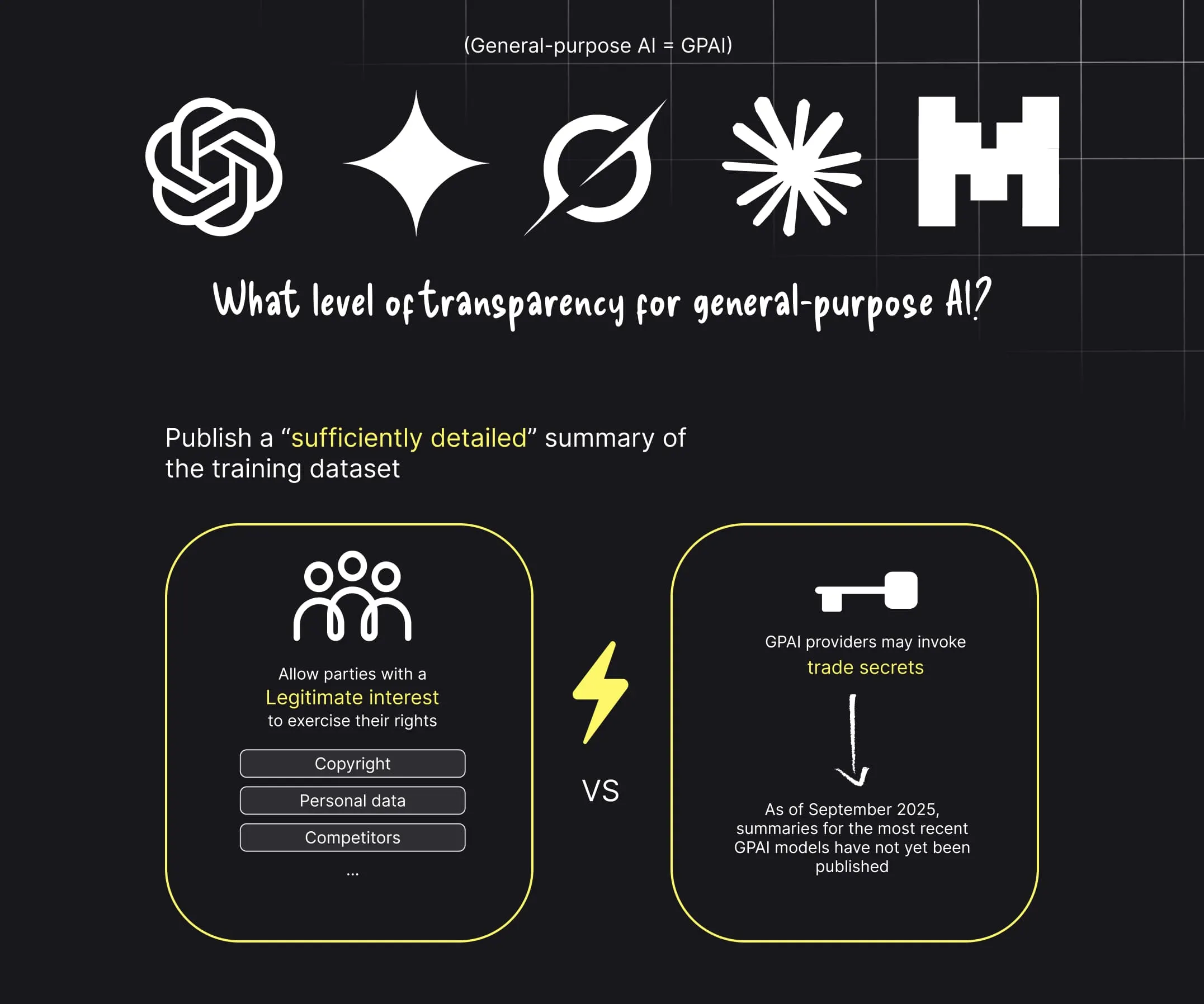

The AI Act also introduces a dedicated framework for General Purpose AI (GPAI), including large language models. These models must provide sufficiently detailed summaries of their training data, respect copyright law, conduct safety testing, and declare models that pose systemic risk due to their scale or computational power.

Although some implementation details are still being clarified, one principle is already clear: large-scale AI systems can no longer operate in total opacity within the European market.

Enforcement of the AI Act will be overseen by a European AI Office. Implementation follows a phased timeline: early bans on prohibited practices, followed by GPAI obligations, and finally full compliance for high-risk systems over the next two to three years.

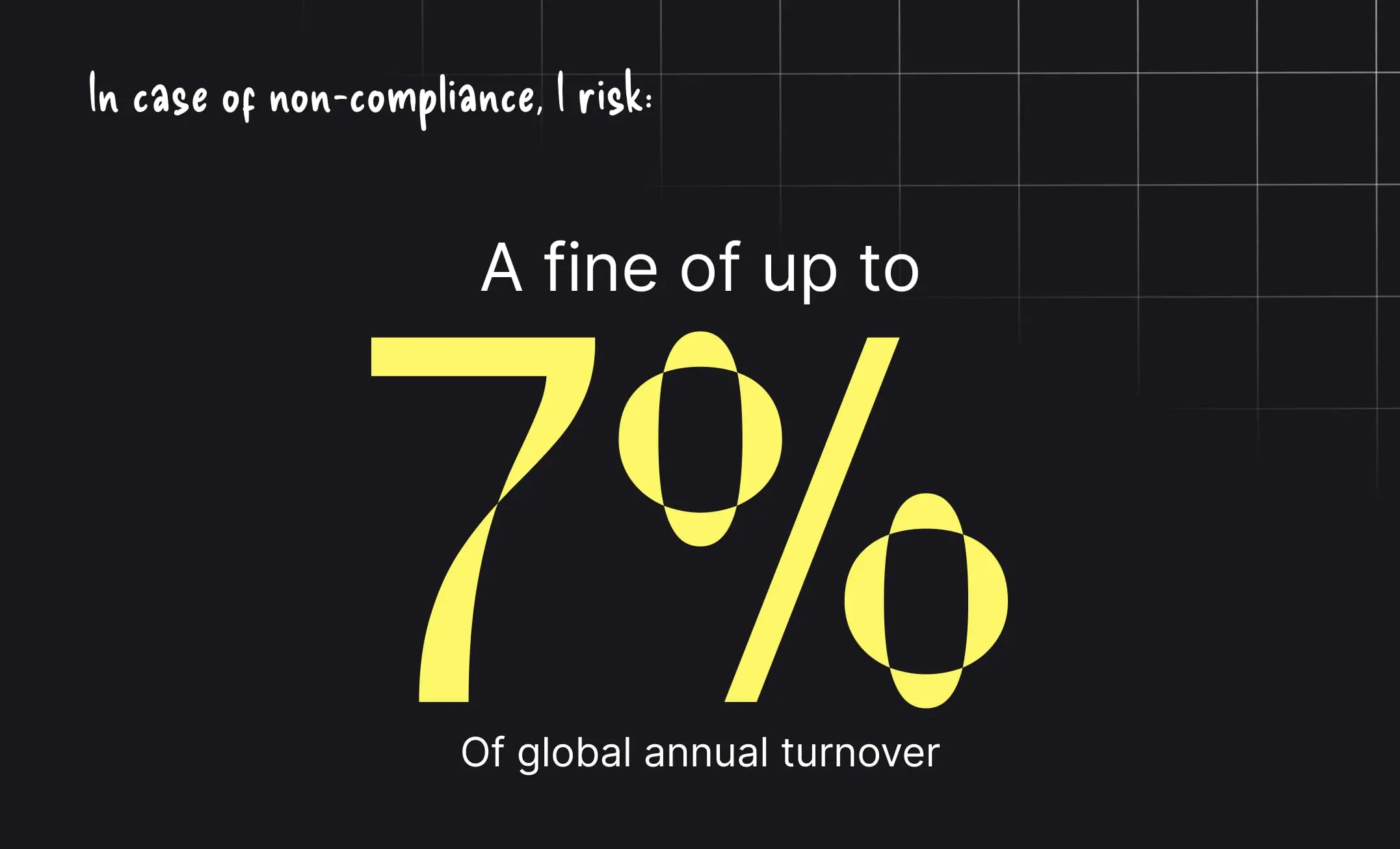

Fines can reach up to 7% of global annual turnover, placing the AI Act on par with the GDPR in terms of financial and reputational impact.

The AI Act does not signal the end of AI in enterprise environments. It marks the end of uncontrolled AI. Organizations that invest early in data structuring, decision traceability, and human oversight will not merely achieve compliance. They will turn regulatory constraints into a durable strategic advantage.

Move to document automation

With Koncile, automate your extractions, reduce errors and optimize your productivity in a few clicks thanks to AI OCR.

Resources

Yann LeCun’s vision for the future of AI, beyond LLMs and AGI.

Comparatives

How invoice fraud works, the most common red flags, and why basic controls are no longer enough.

Feature

Why driver and vehicle documents slow down driver onboarding at scale.

Feature