How invoice fraud works, the most common red flags, and why basic controls are no longer enough.

Feature

Dernière mise à jour :

January 30, 2026

5 minutes

Language models dominate today’s AI landscape. Yet this trajectory is being challenged by a radically different vision.

Yann LeCun’s vision for the future of AI, beyond LLMs and AGI.

Over the past two years, language models have become the dominant reference in artificial intelligence. Their ability to generate text and code has fueled the belief that scaling model size, data, and compute would eventually lead to human-level intelligence.

This trajectory, now widely embraced by the industry, rests on an assumption that is rarely questioned. For Yann LeCun, LLMs are not a natural step toward advanced intelligence. Instead, they expose a structural limitation of current AI systems: their inability to understand the real world beyond textual representations.

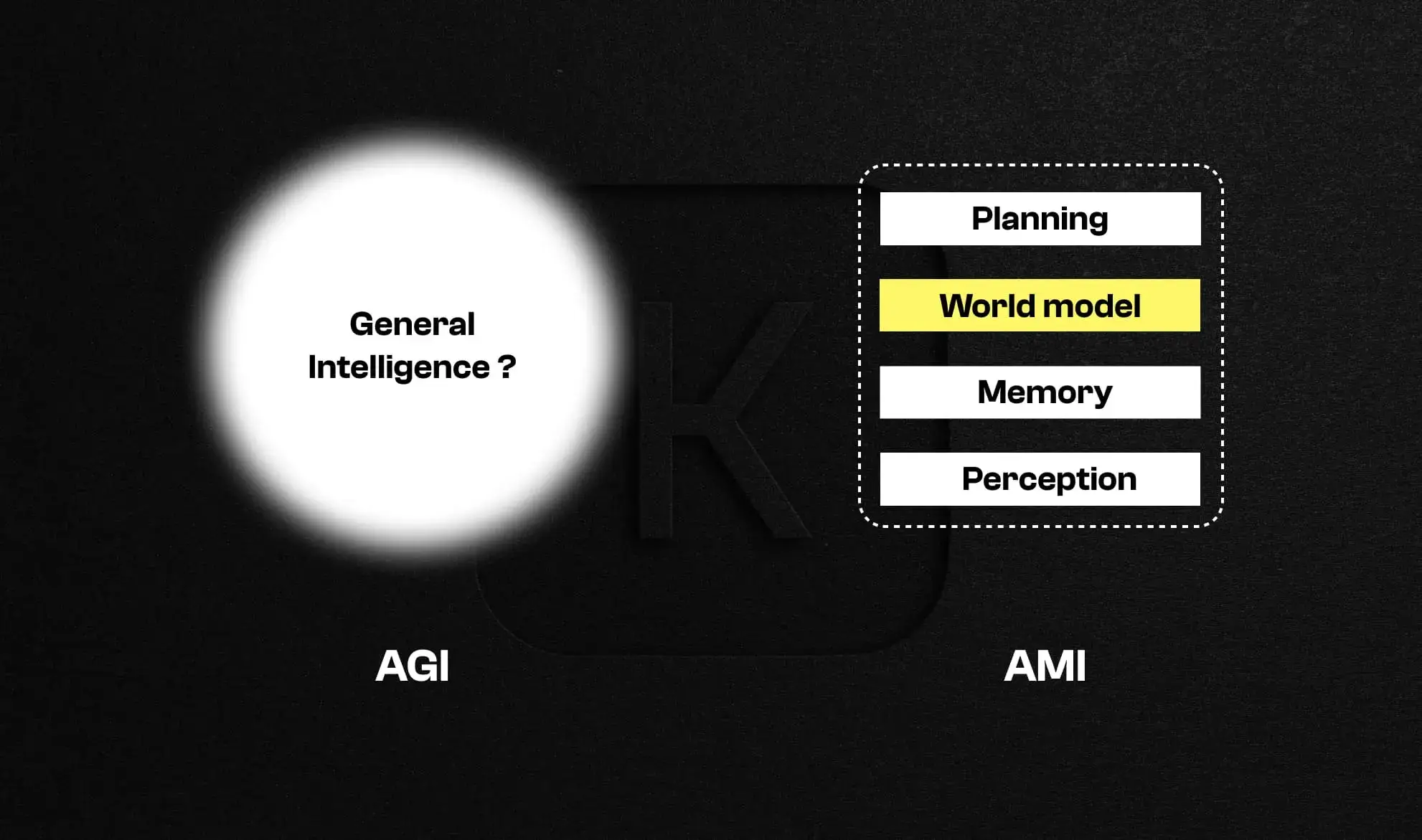

The term AGI, or Artificial General Intelligence, suggests the idea of a universal intelligence capable of understanding and adapting to any situation. According to Yann LeCun, this concept is built on a fundamental misunderstanding.

Human intelligence is not general. It is deeply specialized, shaped by perception, action, memory, and continuous interaction with a physical environment. Talking about AGI projects a misleading abstraction onto systems that share neither our cognition nor our relationship with the world.

LeCun prefers the term AMI, for Advanced Machine Intelligence, or HLI, Human-Level Intelligence. This choice is not semantic. It reframes research around concrete capabilities: perceiving, planning, and reasoning based on a model of the world, rather than chasing an ill-defined notion of general intelligence.

Words shape scientific goals. In that sense, the obsession with AGI often obscures the real technical bottlenecks facing contemporary AI.

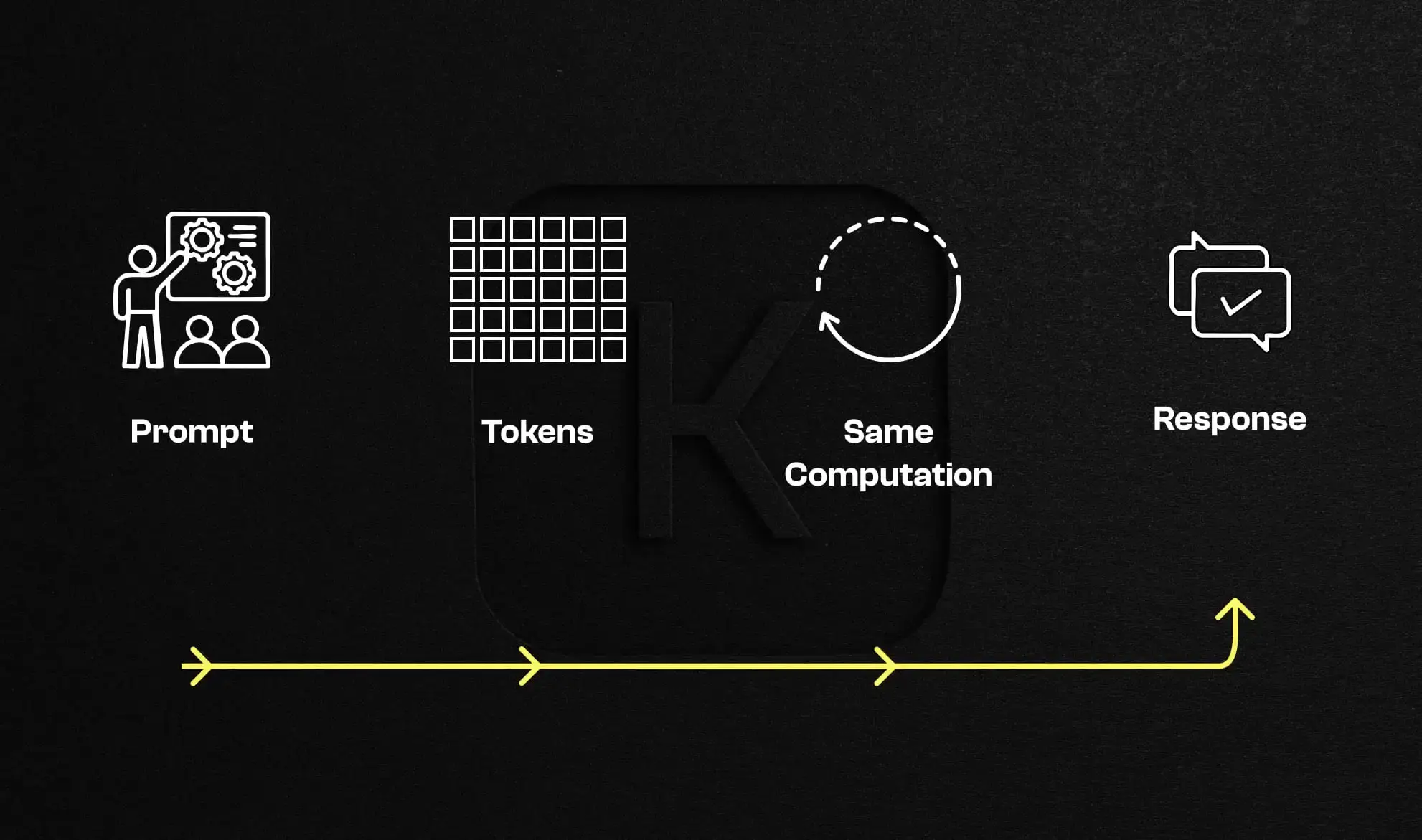

All large language models rely on a simple principle: predicting the next token based on previous tokens. Trained on massive text corpora, they capture impressive statistical regularities and generate responses that often appear coherent.

This effectiveness should not be confused with an understanding of the world. The model manipulates linguistic representations only. It has no notion of objects, no physical causality, and no internal representation of reality.

One often overlooked aspect is computation. To generate each token, an LLM applies a fixed amount of computation. Simple and complex problems are treated in exactly the same way. There is no mechanism that allows the model to allocate more resources to harder situations.

When LLMs appear to reason, they are typically replaying learned patterns. This apparent intelligence quickly breaks down as soon as a problem deviates slightly from the training distribution.

The Moravec paradox highlights a counterintuitive reality: tasks humans perform effortlessly are often the hardest to automate, while certain complex intellectual tasks are relatively easy for machines.

An AI system can solve advanced equations, draft legal text, or analyze financial data. Yet it still struggles with basic actions such as manipulating objects, anticipating physical interactions, or understanding what is possible or impossible in the real world.

Formal reasoning is a relatively recent cultural invention. It relies on explicit symbols and rules. Common sense, by contrast, is the product of millions of years of evolution and learning through interaction.

LLMs excel in domains rich in text and explicit rules. They fail where intuition, perception, and implicit understanding are required.

This gap is not due to an abstract superiority of human intelligence, but to how it is constructed.

A child learns about the world without reading manuals. Through observation, experimentation, failure, and correction, they develop an intuitive understanding of complex concepts such as gravity, object permanence, and causality.

This ability relies on direct interaction with the world, combined with persistent memory and an internal representation of reality. This is precisely what current AI systems lack.

Even when trained on the entirety of publicly available internet content, LLMs only access an indirect description of the world. Text does not capture physical continuity, real-world constraints, or embodied experience.

This gap explains why simply increasing textual data is insufficient to overcome the fundamental limitations of today’s AI.

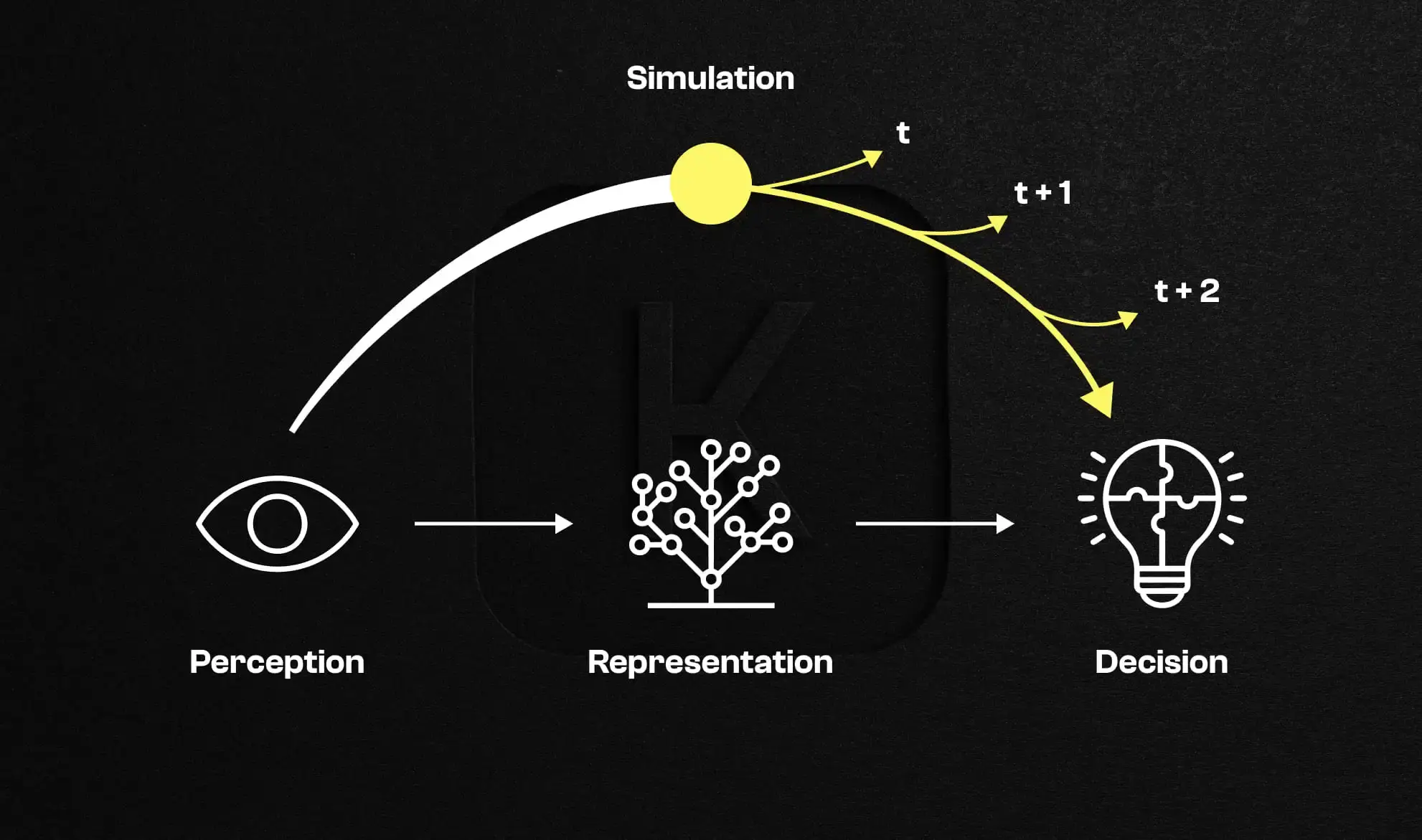

For Yann LeCun, a truly advanced AI must be able to build an internal model of the world. This world model represents the state of reality, imagines possible futures, and evaluates the consequences of actions before they are executed.

This approach fundamentally differs from generative modeling. The goal is no longer to produce plausible outputs, but to simulate reality in order to guide decision-making.

A world model integrates perception, representation, and prediction into a continuous loop. The system observes the world, builds an abstract representation, simulates multiple future scenarios, and selects the most appropriate action based on objectives and constraints.

This internal simulation mechanism, central to human and animal reasoning, is what language models currently lack.

Understanding the world is not just about internal models. It also requires rethinking architectures themselves.

Generative models aim to reconstruct data, whether text, images, or video. While effective for content creation, this approach fails to extract the abstractions required to understand the world.

Predicting pixels or words is not enough to capture underlying causal relationships.

LeCun argues for architectures capable of representing what is relevant and predictable while ignoring noise. This ability to abstract is essential to move from perception to understanding.

JEPA architectures focus on predicting abstract representations rather than generating raw outputs. They allow systems to measure the compatibility between a world state and a goal, then optimize a sequence of actions.

This form of inference through optimization brings AI closer to human reasoning by enabling planning and anticipation.

By embedding explicit objectives and guardrails, this approach enables the design of more controllable systems that can respect constraints while pursuing goals.

Beyond research, Yann LeCun emphasizes the importance of open source. AI controlled by a handful of centralized actors would pose major risks to sovereignty, linguistic diversity, and democracy.

Developing open architectures is a necessary condition for a distributed and pluralistic AI future.

Before reasoning, an AI system must perceive accurately. In the real world, data is imperfect, noisy, and heterogeneous. Documents, in particular, are one of the first domains where this understanding is put to the test.

The line between spectacular AI and truly operational AI often lies here: understanding reality faithfully before attempting to automate it.

The future of artificial intelligence will not be determined solely by model size or generative quality. It will depend on systems’ ability to understand the world, build coherent internal representations, and act in a reasoned manner.

The path defended by Yann LeCun is more demanding and slower, but likely more robust. It reminds us of a simple truth often overlooked: before imitating human intelligence, we must first understand how it is built.

Move to document automation

With Koncile, automate your extractions, reduce errors and optimize your productivity in a few clicks thanks to AI OCR.

Resources

How invoice fraud works, the most common red flags, and why basic controls are no longer enough.

Feature

Why driver and vehicle documents slow down driver onboarding at scale.

Feature

How weak technical signals reveal document fraud risks.

Feature